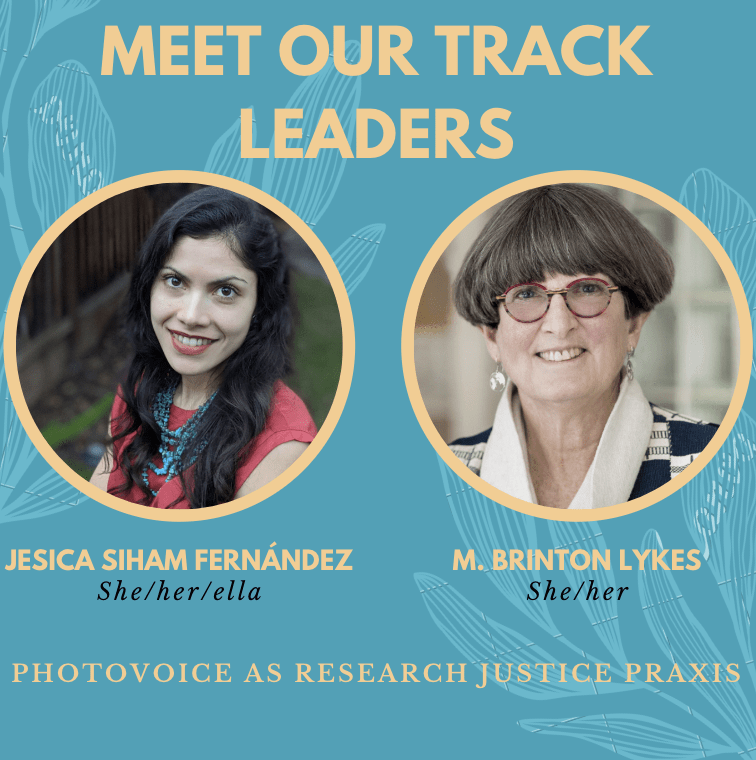

Track Leaders:

Jesica Siham Fernández & M. Brinton Lykes

For the conference, “30 years of photovoice: Past, present and future,” we asked our track leaders to share with us some of their expertise and experiences. We started with the Photovoice as research justice praxis track with Jesica Siham Fernández and M. Brinton Lykes. To learn more about the conference visit our website: www.photovoiceconference.com.

Jesica Siham Fernández

Jesica Siham Fernández is a community-engaged researcher and teacher-scholar, whose work is grounded in a decolonial feminist praxis oriented toward, and in alignment with, participatory action research paradigms. Jesica utilizes photovoice as a pedagogical and methodological tool to foster the sociopolitical development and wellbeing of youth, students, and Latinx communities in their struggles toward liberation, healing, and transformative justice. She is currently an assistant professor of Ethnic Studies at Santa Clara University, and the author of “Growing Up Latinx: Coming of Age in a Time of Contested Citizenship” (NYU Press).

What drove you to use photovoice or participatory photography and what motivated you to stay?

I was introduced to photovoice as an undergraduate student at the University of California Santa Cruz, working in collaboration with a community of residents living in an unincorporated area. As part of this project we facilitated opportunities for community members who joined our participatory action research project to document their community and neighborhood experiences — the challenges, problems and issues, alongside the strengths and uniqueness of living in this unincorporated, under-resourced and institutionally marginalized area. What community members could not articulate into words, they were able to to capture with disposable cameras — disposable cameras!! When I tell my students about my first experiences with photovoice and photographs in the context of community based participatory and engaged action research they are amazed that we were able to create a photo exhibit or photovoice project exhibit with photographs taken with a disposable camera. So, the power of adding stories and narratives to photographs taken by communities who would otherwise remain on the margins of telling and documenting their story, and thereby leveraging their resources and collective power to bring about systemic social change in their neighborhood and living environment called me into becoming a photovoicer — or using photovoice a methodology, pedagogical tool and praxis to bring about transformative social change, justice and liberation with systems impacted communities.

What is one piece of advice you would give to someone new to photovoice?

Be like water; adapting, flowing, and nursing. Adapt to the conditions, context and circumstances of where your research collaboration and partnerships are taking place. Meet communities where they are and their needs based on their terms. Flow, go with the flow. Yes, have a plan, and seek to pursue it — and also be open of heart and mind and experience to, again, adapt to the communities needs and desires — their hopes and dreams. And nourish — create opportunities, cultivate and foster relationships with communities that are grounded in relationality, solidarity and accompaniment. In other words, that will facilitate communities coming to see themselves as powerful, agentic and with the capacities to be the ones to lead and determine the process, trajectories and conditions to bring about change and liberation.

Is there a specific way you’d like to see photovoice implemented that hasn’t been done before?

With the use of technology and social media, it would be very interesting to see how photovoice is being adapted by youth or generations engaged in these technological innovations. I don’t desire to see photovoice implemented in any one specific way; rather I hope that we, as researchers or photovoicers, can remain open and adaptive in our methods and praxis to support how communities wish or desire to record, document and showcase their stories and lived experiences. I am not the most technology oriented person, or active on social media; however, when it comes to supporting what the community desires I’ll jump on the social media, Twitter, Instargram wagon.

When working on a photovoice or participatory photography project how do you ensure you are not speaking for or over the communities you are supporting?

I strive to follow the motto “Nothing about Us, without Us.” This guides my praxis and ethical values toward supporting communities in what it is they want to document, examine, analyze and then ultimately disseminate and share with others. What this also involves is creating intentional, meaningful and purposeful opportunities for communities to be involved at every step of the research or collaboration process. Some of the communities with whom I learn, engage and connect with are communities wherein I am a member of and hold a bit of an intersectional dual positionality. In these instances it is fundamental for me to listen, learn/unlearn, and embody and ethical reflexive praxis of relationality and advocacy that is active in supporting what the community wants to showcase. In these instances I’m mostly asking questions to foment deeter reflection, dialogue and action.

M. Brinton Lykes

M. Brinton Lykes, PhD, is Professor of Psychology and Co-Director of the Center for Human Rights and International Justice at Boston College, USA. Her long-term, anti-racist feminist activist scholarship incorporates the creative arts and onto-epistemologies of original peoples to accompany women and children’s: (1) rethreading of life in the wake of racialized and gendered violence and in post-genocide transitional justice processes; and, (2) migration and post-deportation human rights violations and resistance. She has published extensively, including the co-editing of four books and co-authoring of four others, as well as serving as co-editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Transitional Justice. Her website is tinyurl.com/mbrintonlykes

What drove you to use photovoice or participatory photography and what motivated you to stay?

I met Caroline Wang through Abby Stewart when both were at UMI and Caroline was visiting family in the greater b Boston area. She joined me in a PAR class at BC and spoke about her work including sharing the 1995 Visual Voices book by the Women of Yunnan Province. I was deeply struck by the contrasts/contradictions of the ways in which students and others interpreted the images w/o the words and the meanings attributed by the women of Yunnan Province through photo-voice. I had been working in Guatemala for almost a decade by then, engaging in creative workshops using drawing, collages, theater, creative storytelling with community-based health promoters and had recently begun to work with rural women in Chajul. Distance were significant between villages and the town and transportation mostly on foot. I took the book to Chajul with me one summer to share with the women I was working with and using photos seemed to me like a resource for giving continuities to workshops that folks could not attend in sequences. But when I shared the book with the women there and told them that rural women like themselves had taken the pictures they were stunned – and suggested that they wanted to do it too… Thus unfolded a several year process of developing a project grounded in the previous several years of creative workshops and informed by the signing of the Peace Accords in 1996 that permitted additional possibilities of documenting stories of survivance and protagonisms towards taking actions for buen vivir in rural Guatemala. In 2000 these women published there Voces e imagenes, documenting their experiences of the armed conflict, their recovery/rethreading of traditional beliefs and practices in the wake of massacres, coupled with economic development projects that they were undertaking as a group of women that had become an NGO.

What is one piece of advice you would give to someone new to photovoice?

When I began this work there was little to no digital photography and we used point and shoot cameras with film that had to be taken to Guatemala City to be developed (a nearly 12 hour bus ride) and then images brought back to the town, etc. New technologies have created multiple diverse expectations, knowledges, skills, etc. and one needs to think about these options both in terms of the community/NGO/school, etc. with whom one will be working, the audience(s) one hopes to reach, the finances one can access, etc. Also there are many different understandings of what constitutes a photovoice project and in what ways it is or is not a PAR process – and what kinds of commitments participants and/or co-researchers are able to make to these processes vis-a-vis participation and actions for change, if/when these are PAR processes/projects. Equally important are the possibilities and limitations of photographs (or other mechanisms for recording/documenting) in the cultural, political, gendered and racialized contexts in which one is hoping to work. These are among multiple issues/concerns/questions that emerge as one engages in photovoice and can be thought about – although not resolved – prior to undertaking a project/process.

What has been a favorite photovoice or participatory photography project of yours? Would you be able to share any project photos with us?

I have learned from and enjoyed all of them. Something that I have found challenging in almost every project/process has been a tension from participants who experience themselves to be “good” or “better” or “excellent” photographers and who seek to exhibit, include in books, etc. “the best” pictures photographically – from their “expertise”. Not having such expertise I have never felt that photovoice was about “the best” picture, etc. but rather about all participants being able to share their work in whatever is the outcome. Also, much of my work has been focused on group processes, shared analyses, building community towards taking actions for change – so less individualistic and more collaborative – and therefore I have emphasized inclusiveness … The priority of some folks who are drawn to photovoice see it as a resource to teach photography skills, to demonstrate photographic expertise – especially, I think – through youth work – and thus it is challenging to think about the breadth or scope of all that is “included” in the practice, theorizing, etc. of “photovoice” 30 years in…

In terms of images, the images from the Chajul book are online (with the permission of the women there) at tinyurl.com/mbrintonlykes I have posters designed by PhotoVoice project in post-Katrina NOLA and from work in the greater Boston area with/by students. I am grateful to Shoshi Kessi’s initiatives with students in South Africa that inspired me to use a mini-photovoice process in teaching undergraduates at Boston College and I have been stunned at what I have learned about their lives through these processes in the past several years. Some of those images are also available as well as collages that other students have crafted in projects that are loose iterations from the photovoice and photoPAR processes in which I have been engaged over the years.

What lessons have you learned throughout your career?

Another lesson I have learned from multiple PAR processes and exchanges with folks who are NOT based in a university or other academic context is that one’s context – and audience – deeply informs not only what one does with/through photovoice but how one presents it, whose work it is and how the work is framed. This is not necessarily a problem but it is critical to think

What are the most critical changes we need to make to photovoice and participatory photography to face the future effectively?

I think it is very challenging to know how we are using these terms and what they mean… and in what ways it matters… On another note, I think that to the extent to which folks are seeing photovoice as a research process in which there is “data” and in which there are “findings” that inform knowledge(s) and/or actions, we are challenged to think about how we analyze the images, who does it, and why, that is, towards what ends. In multiple contexts the images plus captions under them have been critical in community education contexts but not necessarily “research” in any classical sense of the term. Is that a problem?

When working on a photovoice or participatory photography project how do you ensure you are not speaking for or over the communities you are supporting?

This is a critically important and challenging dimension of all PAR work including photovoice and photoPAR. And I find that it inflects itself and/or appears in different ways in different moments in the process. Initially it is all about the focus of the project, how you determine what the issues are on which the collaborators/partners/co-researchers want to focus. And issues of how many pictures and how to process the photos once taken… and then how to document the analyses, recognizing that different ones of us participate in very diverse ways and some talk more than others, etc. And then it’s about decisions about which photos and stories/narratives/voices to include in whatever the public presentation is, etc. I find that trying to keep notes about the process and about my own participation in it is very important. And working with another person contributes to that process. And then despite all efforts sometimes I see things in hindsight that I could not see at the time and how my participation may have overtaken that of some of my partners. Also, in terms of whose names are attached to the work, there are many complex and ethical issues related to this particularly if you are doing research in any way that has to be approved by an IRB, etc.